Bad Bunny, Everywhere and Nowhere at Once

BY: OSVALDO ESPINO

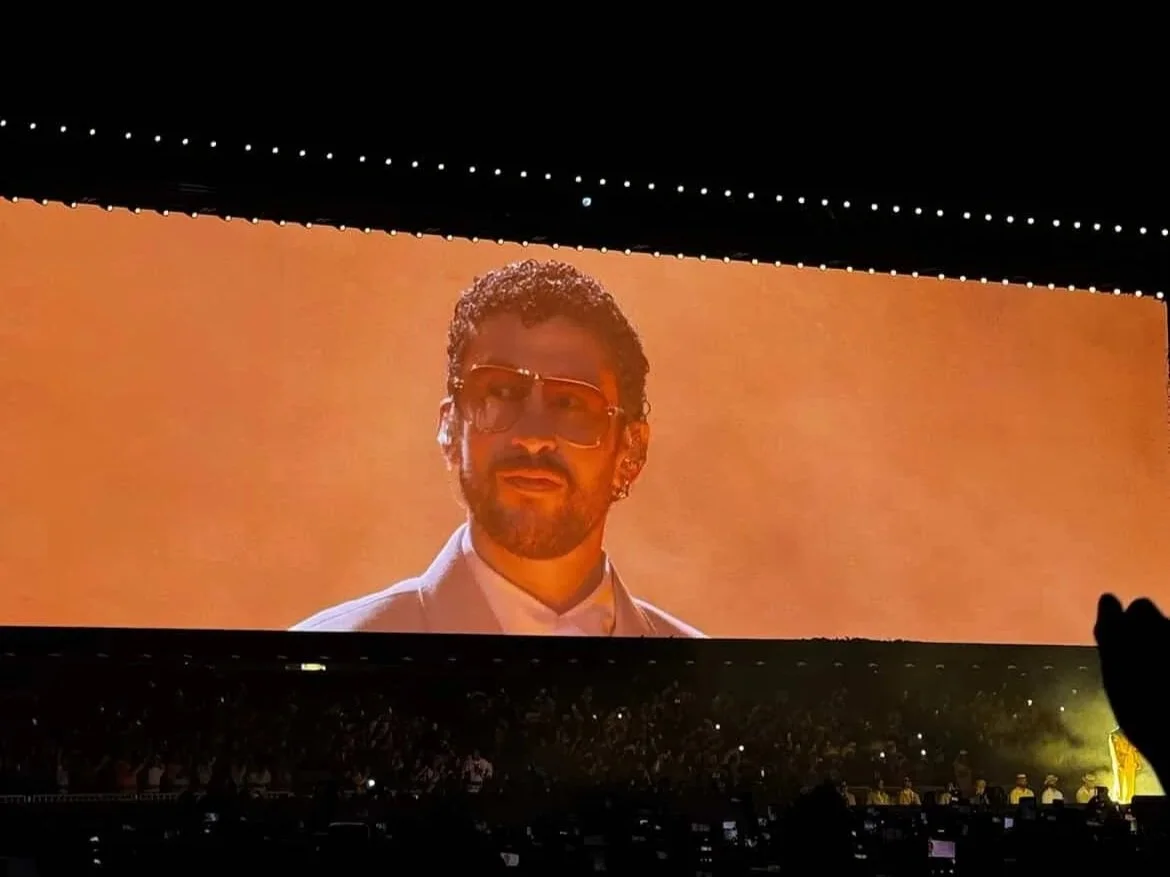

In 2025, Bad Bunny arguably cemented himself as the artist of the year with the release of DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, an album that quickly became one of the most critically and commercially acclaimed projects of the year. Dropping early in January, what followed was not just an album cycle, but a sustained cultural moment: months of hype, a historic residency in Puerto Rico, and a global tour that has since taken over Spanish-speaking countries and extended far beyond them.

Photos taken on iPhone

When we attended one of the Mexico City dates, part of an eight-night run at Estadio GNP Seguros, the scale of what Bad Bunny has become was impossible to ignore. While his Puerto Rico residency reportedly welcomed around 20,000 people per night, the Mexico City shows operated on an entirely different level. According to figures from Ocesa, more than 520,000 people attended across the eight sold-out dates, with the final shows on December 19, 20, and 21 selling out well in advance. In a city synonymous with massive concerts and historic performances, Bad Bunny now ranks as the third artist with the most shows ever held at the legendary stadium formerly known as Foro Sol, trailing only Shakira, who holds the record with 12 shows, and Mexican powerhouse Grupo Firme, with nine.

For a Puerto Rican artist not of Mexican descent, that achievement carries real weight. This was not Mexico City “hosting” Bad Bunny. It was Mexico City embracing him, integrating him into its cultural lineage, and elevating him into its musical history. That distinction matters.

Benito! Hermano! Ya eres Mexicano!

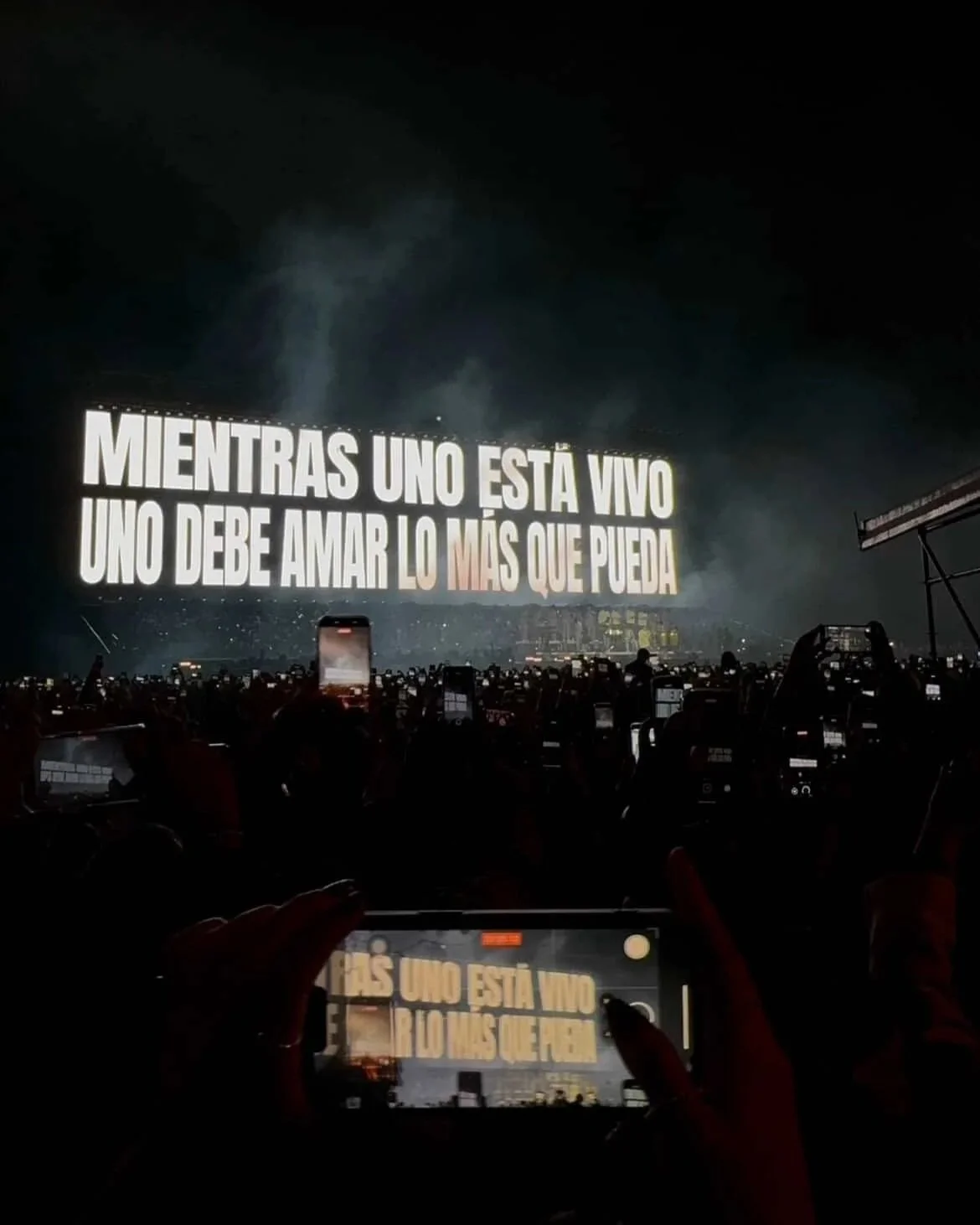

The crowd reflected that embrace. Outside the stadium, fans lined up as early as 4 p.m., buying off-brand merch, sharing drinks, and waiting patiently for general admission. Inside, the energy felt less like a concert and more like a communal release. Fans had traveled not only from across Mexico, but from the United States and other countries as well. Spanish flowed freely. Families, young couples, and groups of friends filled the stands. There was no tension in the air, no sense of being watched. Just joy.

That sense of belonging peaked on Monday, December 15, when Grupo Frontera joined Bad Bunny onstage as a surprise guest. The Mexican-American supergroup emerged to the roar of 66,000 people, according to Ocesa, as fans raised their phones to capture the moment. Together, they performed the Tex-Mex cumbia “Un x100to,” blending regional Mexican music with reggaetón and Caribbean salsa into a single, unforgettable collaboration. Led by vocalist Adelaido “Payo” Solís III, Grupo Frontera became the second guest of the Mexico City run, following Colombian artist Feid, who had appeared earlier in the week from the alternate stage known as La Casita.

It was more than a guest appearance. It was a cultural convergence. Borders blurred. Genres collapsed into one another. The moment felt intentional, symbolic, and deeply rooted in shared experience rather than novelty.

By the end of the run, the magnitude of what Bad Bunny had accomplished became undeniable. His DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS World Tour generated an astonishing US$86.7 million across just eight shows at Estadio GNP Seguros, officially becoming the highest-grossing concert series ever hosted at the venue. In doing so, he broke a record previously held by Shakira, a benchmark that once felt untouchable. This was not just success. It was infrastructure bending to meet Latino demand.

That number tells a story the United States often refuses to acknowledge. Latino audiences are not a niche market. They are an economic engine. Mexico City didn’t hesitate to invest in that reality. It trusted Bad Bunny with scale, with legacy, and with the responsibility of carrying half a million people through eight nights of collective joy. The city benefited accordingly. Hotels filled. Restaurants stayed busy. Transportation systems operated at capacity. Entire neighborhoods felt the impact.

And that is where the contrast becomes unavoidable.

What the United States is missing is not just a tour stop. It is missing one of the most electric live experiences happening anywhere in the world right now. It is missing the chants, the communal release, the joy that fills stadiums night after night across Latin America. And it is missing the revenue that comes with it. By its own doing, the country has placed itself outside the gates of a global cultural moment.

Bad Bunny has famously avoided touring the United States, citing fears that ICE could be present outside venues, potentially harassing or targeting undocumented fans. In a political climate where Latino identity is routinely scrutinized, politicized, and framed as a problem to manage, his absence feels less like a personal choice and more like an indictment. A figure like Bad Bunny does not simply exist in this environment as a pop star. He becomes a conduit. A vessel through which frustration with immigration policy, cultural erasure, and the current administration is expressed openly, loudly, and in Spanish.

The irony is striking. The United States is eager to claim Bad Bunny when it needs global relevance, when the Super Bowl requires spectacle, ratings, and cultural credibility. But when it comes time to protect the communities that sustain him, the country hesitates. In doing so, it forfeits not only cultural goodwill, but tangible economic growth. American cities are missing out on the kind of tourism surges and revenue booms that Mexico City embraced without fear.

Elsewhere, the equation is understood. Latino culture is not treated as a liability. It is treated as a catalyst. It fuels nightlife, tourism, and global influence. It turns concerts into pilgrimages and artists into ambassadors. When allowed to exist freely, it pays dividends far beyond the stadium walls.

The album itself reflects that tension. DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS operates as both a deeply personal project and a pointed critique of American tourism and the exploitation of Puerto Rico’s land and resources. It is a defiant statement wrapped in melody. One that Latinos across borders have latched onto because it mirrors their own experiences of displacement, pride, and survival. What we witnessed in Mexico City felt like the physical manifestation of that message, a place where Spanish is not an accommodation, but the default.

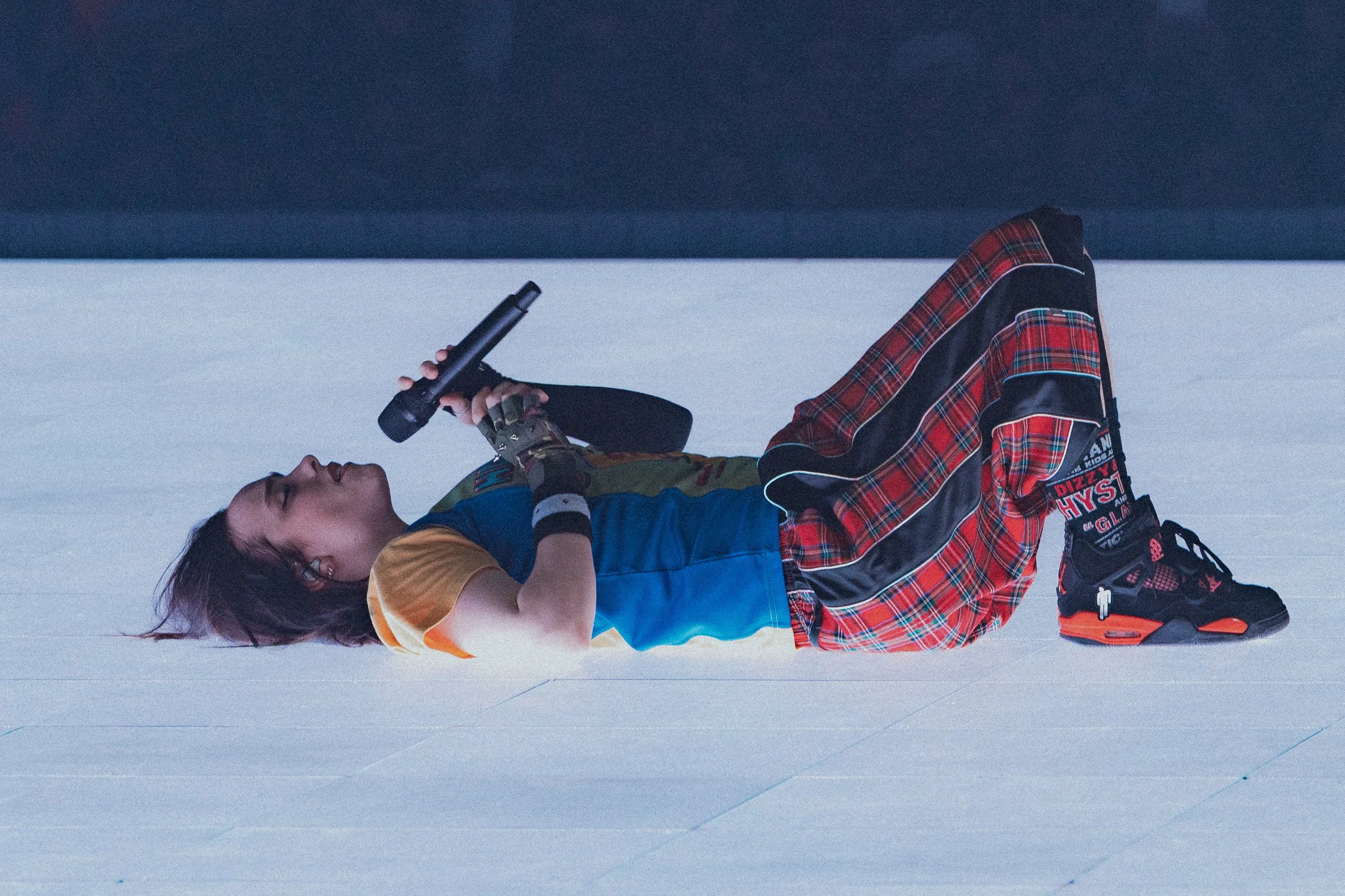

The production of the show reinforced that idea. Bad Bunny performed across two stages: a massive, flat main stage and La Casita, the now-iconic structure that has been plastered all over social media. Throughout the Mexico City dates, La Casita became a symbolic home, filled with artists and cultural figures from across the region. A house that moved freely where people often cannot. A reminder of what belonging can look like when it is not restricted by borders or bureaucracy.

The setlist matched that ambition. Spanning every era of his career, the show was so expansive that Bad Bunny now performs one unique song per night, each played only once throughout the tour. On our night, that moment came with Grupo Frontera. Other nights featured appearances from Feid, Julieta Venegas, pioneers of corridos tumbados like Natanael Cano, and even a long-awaited reunion with J Balvin, closing the chapter on years of tension.

By the time Bad Bunny transitioned from perreo-heavy tracks into full salsa moments that had the entire stadium dancing, it was clear that this project had grown into something far larger than an album cycle. It represents a shift in power. Mainstream music is no longer exclusively Anglo, Western, or American. It is global, multilingual, and increasingly shaped by Latino voices.

In February, Bad Bunny is set to become the first Latino artist to headline the Super Bowl. Watching him in Mexico City, embraced by tens of thousands without hesitation, makes that milestone feel both overdue and revealing. Abroad, he is trusted, celebrated, and empowered. At home, his community is still asked to justify its presence.

Bad Bunny now stands at the center of that contradiction. Everywhere in the world, yet intentionally absent from the country that wants his spectacle without his people. History will remember where this moment was welcomed and where it wasn’t.